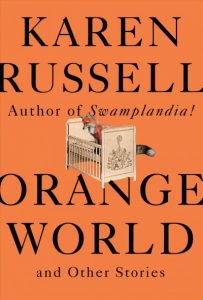

“Karen Russell’s comedic genius and mesmerizing talent for creating outlandish predicaments that uncannily mirror our inner in lives is on full display in these eight exuberant, arrestingly vivid, unforgettable stories. In“Bog Girl”, a revelatory story about first love, a young man falls in love with a two thousand year old girl that he’s extracted from a mass of peat in a Northern European bog. In “The Prospectors,” two opportunistic young women fleeing the depression strike out for new territory, and find themselves fighting for their lives. In the brilliant, hilarious title story, a new mother desperate to ensure her infant’s safety strikes a diabolical deal, agreeing to breastfeed the devil in exchange for his protection. The landscape in which these stories unfold is a feral, slippery, purgatorial space, bracketed by the void—yet within it Russell captures the exquisite beauty and tenderness of ordinary life. Orange World is a miracle of storytelling from a true modern master.”

“Karen Russell’s comedic genius and mesmerizing talent for creating outlandish predicaments that uncannily mirror our inner in lives is on full display in these eight exuberant, arrestingly vivid, unforgettable stories. In“Bog Girl”, a revelatory story about first love, a young man falls in love with a two thousand year old girl that he’s extracted from a mass of peat in a Northern European bog. In “The Prospectors,” two opportunistic young women fleeing the depression strike out for new territory, and find themselves fighting for their lives. In the brilliant, hilarious title story, a new mother desperate to ensure her infant’s safety strikes a diabolical deal, agreeing to breastfeed the devil in exchange for his protection. The landscape in which these stories unfold is a feral, slippery, purgatorial space, bracketed by the void—yet within it Russell captures the exquisite beauty and tenderness of ordinary life. Orange World is a miracle of storytelling from a true modern master.”

This collection has been on my Must Have list for ages, but if a doubt had risen in my mind during that time as to whether or not I should go ahead and read it, well, the Poets & Writers interview with Karen Russell would have squashed it flat, scraped it up, and duly dumped it somewhere far, far away. An excerpt from that interview is below; I chose this particular Q&A because it touches on the first story in the collection, one that I adored from the sentence level up.

One thing I love about all of the characters in this collection is that, like Angie and Andy in “The Bad Graft,” they’re not wealthy. They worry about money, and they work hard for it. The grifters in “The Prospectors,” Clara and Aubergine, for instance, are as much victims of societal oppression as the twenty-six impoverished men of the Oregon Civilian Conservation Corps who built the grand Emerald Lodge and then died in it when an avalanche swept the building away. On the surface, “The Prospectors” reads like a classic ghost tale, and yet at heart it strikes me as a political story. Do you think of yourself as an overtly political author? Or am I projecting too much?

I don’t think you’re projecting at all, although I rarely have a wholly conscious ambition for a story when I begin, beyond a wish to explore a certain collision of landscape and character and desire. I did have an inkling, when I began “The Prospectors,” that the catalyst for the story would be two young women who were prospectors, treating their future together like speculators, panning for golden horizon light somewhere far from home. And that we’d watch their early hope darken into a kind of desperation, and see how hunger, figurative and literal, can underwrite many forms of denial and delusion.

Shortly after I moved to Oregon I visited the Timberline Lodge on the side of Mt. Hood, “an architectural gem atop a natural wonder,” the showpiece of the Works Progress Administration (made famous by that ominous aerial shot that opens The Shining, to which this story certainly owes a debt). I was so moved by the black-and-white photos of the WPA and CCC crews, these bony young men trying to hoist themselves and the nation out of the Depression by building a fantasy ski resort. These boom and bust cycles in American history fascinate me; today, Oregon’s coastline is haunted by once-bustling ports and timber towns. The Columbia River bar is home to so many shipwrecks it’s known as “the graveyard of the Pacific.” I am always interested in the dreamers who navigate the shoals, who discover, often belatedly, that their dream is poorly suited to the reality in which they find themselves. The West is rich in stories of those dreamers who succeeded, but there are so many nameless others who got mowed under, and today we have a president who talks about “winners” and “losers” as if the entire onus for success or failure is on individuals, when in fact from birth onward the deck is stacked so profoundly against millions of people in our country.

I hope “The Prospectors” has contemporary resonance for readers, both insofar as it explores the way financial insecurity can transform interior and exterior landscapes, and because it looks at the way that women are often tasked with supporting an entire infrastructure in unacknowledged, uncompensated ways (in this story, Aubby and Clara do their “prospecting of the prospectors” by quite strategically propping up male egos and underwriting a ghostly world of male power and ambition, siphoning off wealth’s remainders, long before they are called upon to donate their life force to the phantom lodge and the ghosts inside it, minting them into reality). The precarity of the women’s position on the mountain, the careful way they maneuver through that party, is not so distant, I think, from the existential and economic calculations many women must make today in our tilted world.