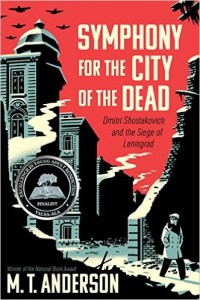

You’re on the hunt for a lighthearted or uplifting book to read while winter wanes; your eager eye has wandered here, to this title by National Book Award winner M.T. Anderson, but I must tell you: Symphony for the City of the Dead is neither lighthearted, nor uplifting. This book, after all, concerns the Soviet Union. It concerns the Soviet Union in the thrall of Stalin’s blood-splattered regime. The NKVD openly stalk the streets here, in these pages. No one is safe or above accusation. In Leningrad (and Moscow, and every expanse of earth contained within the Soviet Union’s borders) during this time, the arts and sciences were at risk of disappearing beneath a pounding fist, a stomping jackboot. There were artists and composers and members of the intelligentsia who persevered in the face of persecution. One in particular, composer Dmitri Shostakovich, takes center stage in this unflinching account of a Great Terror that tests the strength of music’s intrinsic, far-reaching power.

You’re on the hunt for a lighthearted or uplifting book to read while winter wanes; your eager eye has wandered here, to this title by National Book Award winner M.T. Anderson, but I must tell you: Symphony for the City of the Dead is neither lighthearted, nor uplifting. This book, after all, concerns the Soviet Union. It concerns the Soviet Union in the thrall of Stalin’s blood-splattered regime. The NKVD openly stalk the streets here, in these pages. No one is safe or above accusation. In Leningrad (and Moscow, and every expanse of earth contained within the Soviet Union’s borders) during this time, the arts and sciences were at risk of disappearing beneath a pounding fist, a stomping jackboot. There were artists and composers and members of the intelligentsia who persevered in the face of persecution. One in particular, composer Dmitri Shostakovich, takes center stage in this unflinching account of a Great Terror that tests the strength of music’s intrinsic, far-reaching power.

So I’ve told you what Symphony isn’t; as for what it is: Will ‘excellent’ do? From where I’m typing, yes. It will. Heartbreaking also works.

The Soviet Union during Shostakovich’s lifetime was a bleaker than bleak, battered-to-a-pulp place. The horror of it all is unimaginable. The nightmare began before Stalin seized power, and the book goes there, neatly lining up the dominoes that led to the February and October Revolutions of 1917, and to Lenin’s rise on the back of his communist ideals. But when the murder of the Romanov family is relayed in a single, parenthetical sentence, you know that the story Anderson is telling is not theirs, and even though they played a role, it’s not the Bolsheviks’ either. The city of Leningrad, however, is a major character in Shostakovich’s life and in the narrative. Sentences shape streets that wheeze, that wail. Several chapters in you’d swear you can see buildings bruise and bullet holes bleed out at paragraphs’ end. It’s affecting stuff, shudder-inducing. And it’s relentless. That Shostakovich was able to write even a single note, let alone entire symphonies while a world of brutality kept turning outside his door is remarkable.

But then, if that fact seems so unfathomable as to require explanation, there’s this:

“…music itself is a code; how music coaxes people to endure unthinkable tragedy; how it allows us to whisper between the prison bars when we cannot speak aloud; how it can still comfort the suffering, saying, ‘Whatever has befallen you–you are not alone.'”

Symphony marches through WWII, with its eye trained on Leningrad, and on Shostakovich. Anderson briefly takes the reader Stateside to see the effect the composer’s celebrated 7th Symphony had on American audiences; he drops the reader into Germany after Hitler took to his bunker and his gun. He keeps us with Shostakovich and the Soviet people until the end, and by the last page I had long since lost track of the number of the dead. The casualty count was staggering and grievously saddening, and it goes without saying, perhaps, that this book, tone-wise, never lifts itself up from grim–the facts that drive the narrative wouldn’t allow for it. Bearing that in mind, Symphony is very well executed and the details are crisp, sharper than the grainy pictures included throughout.

Titles for further reading and music for suggested listening:

Click on a book or CD cover to be taken to that item’s page in the NOBLE catalog.