There was a bit of a line in Jennifer Senior’s New York Times review of The Man With the Golden Typewriter that drew my eye back to read it again, because, I suppose, I was trying to imagine what a giant stalk of catnip might look like, if it would be Jack-worthy giant or stop short of the clouds, and what about the leaves – would they be an impediment? For climbing purposes, purely. Mostly I went back to that bit of that sentence because Senior pitched it at writers of every ilk and at readers who dig insight into the writing/publication process. I identify as both, so, clearly, Ian Fleming’s letters were meant for me.

There was a bit of a line in Jennifer Senior’s New York Times review of The Man With the Golden Typewriter that drew my eye back to read it again, because, I suppose, I was trying to imagine what a giant stalk of catnip might look like, if it would be Jack-worthy giant or stop short of the clouds, and what about the leaves – would they be an impediment? For climbing purposes, purely. Mostly I went back to that bit of that sentence because Senior pitched it at writers of every ilk and at readers who dig insight into the writing/publication process. I identify as both, so, clearly, Ian Fleming’s letters were meant for me.

I am well familiar with Cinematic Bond. At my father’s insistence and without even token protest or resistance on the part of my young self, I cut my teeth on spy tension and tropes with a Scottish accent echoing in my ear. I gobbled up the 007 films, steering through Lazenby’s forgettable foray, through Moore’s seven film stretch, and Dalton’s and Brosnan’s brief reigns too, until here we are with Craig’s grit and gri–no, not a grin, but his world-class smirk. (And with the irresistible, smart-mouthed charm of a new, cardigan-wearing, Earl-Grey-drinking Q.) But somehow, somehow I managed to plow through my reading life without once picking up any one of Fleming’s Bond novels. That right there needs to be rectified, and will be. At some point. As for the here and now, all this long-winded paragraph is aiming at is: No matter how small the shred, if you know anything at all about Bond, James Bond, you’re equipped with more than you need to read this collection of letters.

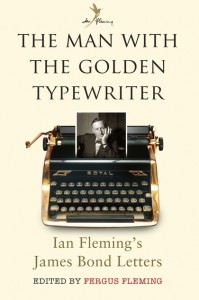

Fergus Fleming–Ian’s nephew, in case the last name prompted conjecture about a familial connection–opens the book with something like a super-condensed biography, or a chapter-long sketch of Ian Fleming’s life. His wartime antics, publishing career, the demise of his bachelorhood, and the many habits (women, cards, imbibing) that Fleming passed along to his greatest creation provide context for the contents of the letters, and, while I’m here, props should be given to Fergus for knowing how to pull out for display the salient points of a well-lived life.* Consecutive chapters lead with a note about the time period during which the letters were written, where in the world Fleming was writing from, but mostly about which Bond book(s) Fleming was typing up on that gold-plated Royal Quiet Deluxe Portable he had smuggled into England. (Customs and their pesky taxes. I tell you, it’s enough to drive a man towards asking a friend to do the dirty work.)

As for the letters, they’re a remarkable mix of ego and insecurity; of living to the fullest extent and digging deep into the creative process; of haggling for more (royalties, a larger first print run, an aggressive marketing campaign next-time-please, etc.) while exhibiting a generosity that was only occasionally reluctant. Included in the book are letters to friends, to the team at his publishing house, to fans (many of whom wrote to correct Fleming on various things, such as French phrasing, the gun in Bond’s hand, and so on), and to news outlets, among other recipients. All too rarely included are the letters he received from the aforementioned individuals. The Man With the Golden Typewriter really is a rather fascinating behind-the-scenes look at the life of a working writer, who, in an attempt to come to terms with the resentment that assailed him courtesy of his pending marriage, happened to give life to arguably the world’s most famous fictional spy.

*Greatest creation holds true, I think, unless you’re a rabid fan of Caractacus Pott, in which case, Up from the ashes!