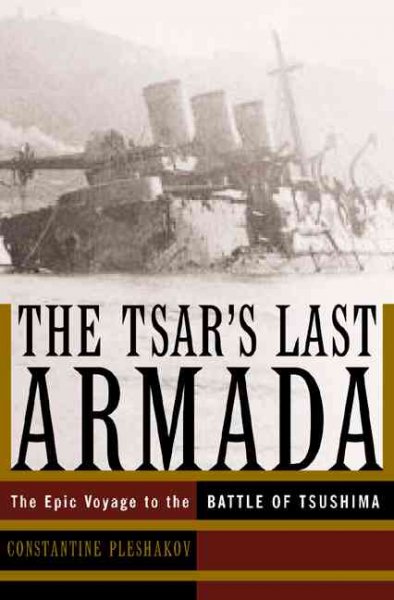

If you are like me you haven’t heard much about the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). Which as I found out is kind of a shame because it really sets the stage for a lot of the wars of the 20th century. Pleshakov’s Tsar’s Last Armada, takes you through the final drama of that war: Czar Nicholas dispatching his fleet from St Petersburg in the Baltic Sea half way around the world to their inhalation at the Battle of Tsushima.

If you are like me you haven’t heard much about the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). Which as I found out is kind of a shame because it really sets the stage for a lot of the wars of the 20th century. Pleshakov’s Tsar’s Last Armada, takes you through the final drama of that war: Czar Nicholas dispatching his fleet from St Petersburg in the Baltic Sea half way around the world to their inhalation at the Battle of Tsushima.

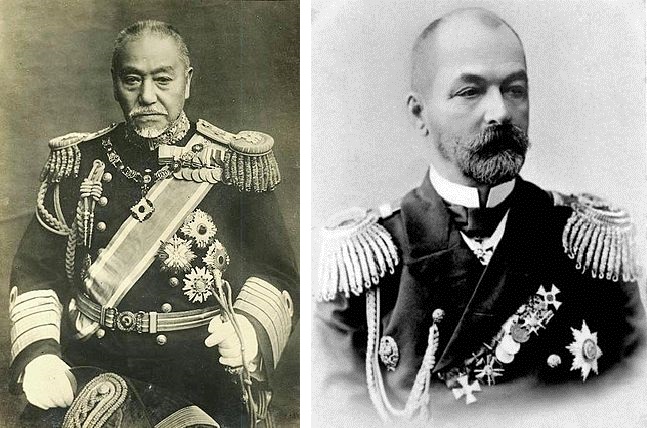

In a nutshell, the Russo-Japanese war was an outgrowth of Russian expansion into Manchuria running up against Japan’s expansion into Manchuria. The official opening of the conflict was a surprise attack by Japanese Admiral Togo Heihachiro on the Russian Navy at Port Arthur (today the Lyushunkou District) with several torpedo boats (one of the first uses of the self-propelled torpedo) on the night of February 8, 1904. Several large warships were damaged. This was the opening of a disastrous campaign for the Russians who were blockaded by land and sea in Port Arthur. In the process of trying to break that blockade the Russian navy took heavy loses against the Japanese navy. The Tsar decided to send a fleet from the Baltic under admiral Zinovy Rozhestvensky to reinforce the beleaguered Port Arthur garrison.

Pleshakov highlights many of the problems encountered by the fleet as it sailed. One of the major ones was coal. Although Russia had allies in the from of France and Germany, the French offered only grudging aid because no one wanted to irritate the British who supported the Japanese. As a result the fleet had continual trouble finding hospitable ports to replenish its coal supply. Another was the constant influx of reports from Russian spies all over the world announcing, falsely, that Japanese agents and/or torpedo boats were waiting in ambush around every corner. This resulted in several confrontations. Finally when Rozhestvensky and Togo’s fleets meet in Battle

Pleshakov has an engaging writing style in engaging and he has a talent for explaining both the complexities of a early 20th century navy without getting bogged down. He also gives the reader a sense of the personalities involved. Rozhestvnsky for example had a tenancy to fly into a rage and throw his binoculars into the sea. On the voyage his staff packed an extra fifty binoculars and worried it wouldn’t be enough. Finally when Rozhestvensky and Togo’s fleets meet in Battle, Pleshakov does an excellent job of describing the movements of all the ships. This is a great military history. This is a great book for anyone interested in the background on the First and even Second World Wars.

Tōgō Heihachirō and Zinovy Rozhestvensky